Imagine you hear a song you loved years ago. The same rush of feeling returns, as if no time had passed since the first time those notes hit you. It’s tempting to believe that this reaction is etched into the brain, as unchanging as stone. For decades, that was the reassuring story of neuroscience: once learned, a memory was thought to sit neatly in place, locked into a fixed neural circuit; a tidy library of patterns, silent until summoned.

The truth, though, is much less tidy.

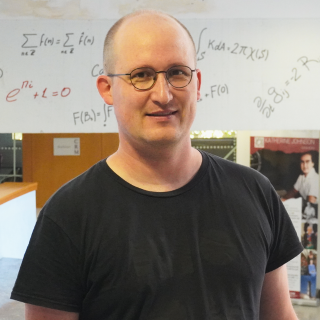

In Current Opinion in Neurobiology, a review titled “Statistical learning and representational drift: A dynamic substrate for memories” challenges that long-standing belief. Written by Jens-Bastian Eppler (Centre de Recerca Matemàtica), Matthias Kaschube (Goethe University Frankfurt), and Simon Rumpel (University Medical Center Mainz), the paper confronts a paradox at the heart of brain science: if neurons and synapses are in constant flux, how is it that perception and memory feel so stable?

That mismatch is what scientists call representational drift. To us, “memories feel stable,” Eppler says, “and in our behaviour they are. If you learn something as a child, you will often remember it for the rest of your life. But we have no idea how this stability emerges.” For a long time, the dominant view was that the brain stored memories in circuits that stayed put, changing only when something new was learned. “Researchers have now found that if you see the same thing on different days, the activity in your brain is different,” Eppler explains. “You look at the red traffic light; you still know what it is, but in your brain, different sets of neurons are active.”

Hints of this phenomenon first appeared in the 2000s, as methods weren’t strong enough to prove it before that. Scientists could only record activity for a single day in an animal before the experiment ended. “Now,” Eppler notes, “we can follow brain activity over longer periods, and everywhere people have looked, there is this representational drift.” The term itself only gained traction in recent years.

“The brain is so unstable, and at the same time, the behaviour is stable. For me, there’s a huge paradox.”

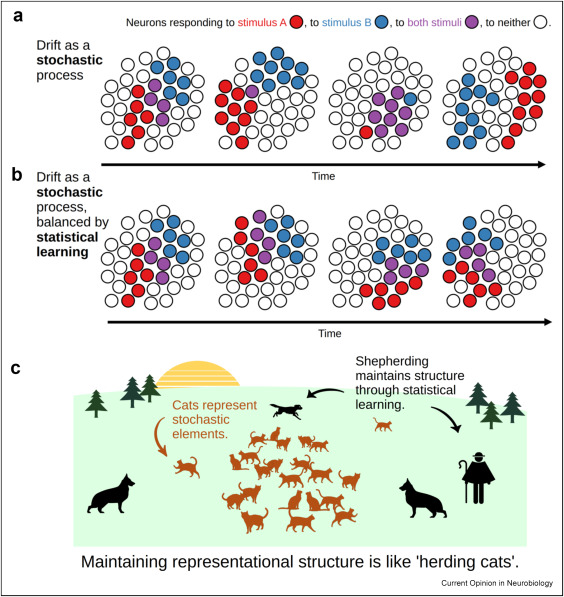

So, what explains the paradox: neurons changing, memories stable? Eppler points to synaptic plasticity, the way connections between neurons constantly shift. “Hebbian plasticity is often described as ‘neurons that fire together, wire together.’ That means that if two neurons are active together, they will form a stronger connection between them. And this is happening all the time in our brain.” Each new sound, image, or movement leaves its trace, altering the network. In the review’s terms, stability reflects a balance between Hebbian learning and stochastic synaptic ‘temperature,’ which sets how much the network wanders.

Over time, some neurons fire for multiple experiences, overlapping patterns reshape the synapses, and the whole system drifts. “If you see something often, then the connections are strengthened a lot,” Eppler says. This is what neuroscientists call statistical learning: the brain quietly tracking how often things occur together, an idea first developed to explain how infants learn language by hearing sounds again and again.

Here lies the key: what remains stable is not the individual activity patterns, but their similarities. As Eppler puts it, “People discovered everything is changing. And then they looked for similarity maps.” He gives the example of colours: “red and orange may activate completely different neurons from one day to the next, but across days, orange is always closer to red than to blue. The similarities are stable, not the activities themselves.”

To explain how order emerges amid chaos, the research team used a very original image: herding cats: “In this metaphor, the cats are the stochastic changes; there’s always something changing randomly. The shepherds that are herding the cats would be the statistical learning. They will never achieve a 100% perfect job; the activities are still changing, but they manage to do well enough. The overall structure of the herd is maintained.” Tellingly, the overall map can re-form after disruptions; even when specific neurons are ablated, the relational structure recovers within days.

To explain how order emerges amid chaos, the research team used a very original image: herding cats: “In this metaphor, the cats are the stochastic changes; there’s always something changing randomly. The shepherds that are herding the cats would be the statistical learning. They will never achieve a 100% perfect job; the activities are still changing, but they manage to do well enough. The overall structure of the herd is maintained.” Tellingly, the overall map can re-form after disruptions; even when specific neurons are ablated, the relational structure recovers within days.

Even emotions like boredom fit into the picture. “Boredom is a very strong negative emotion; if we are bored, we don’t get enough input. And this makes our brain’s memories unstable. The idea is boredom makes us seek new experiences, and then just by the statistics of these experiences, our activity is kept together.” In other words, boredom pushes us back into situations where the shepherd can herd the cats again.

The same framework changes how we think about forgetting. Instead of a flaw, it may be the natural result of drift: random changes slowly erode some traces, while new Hebbian learning overwrites others. “It allows the system to clear out information that’s no longer relevant,” Eppler says.

All of this requires mathematics to make sense. “Some years ago, people could only measure single cells, and then you didn’t need a lot of maths; you could say it’s on, it’s off, you give a firing rate. But now you have these massive recordings of thousands of neurons, you need some clear way to describe them,” Eppler says. “The underlying thing that is generating them is a network. Not every possibility is achievable; it is highly constrained by the network. And here, I think, there’s a huge contribution mathematical concepts can make.”

That contribution is not just technical. It reshapes how we picture memory itself. Not a fixed photograph tucked away, but something more like a melody played by an orchestra in constant flux, with musicians changing seats and instruments but the tune persisting.

“Memories feel stable to us,” Eppler reflects. “But that stability is not because the brain is static. It’s because it keeps learning, all the time, even when nothing new seems to happen.”

Citation:

Eppler, J.-B., Kaschube, M., & Rumpel, S. (2025). Statistical learning and representational drift: A dynamic substrate for memories. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 87, 102022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2025.102022

crm researchers

Jens-Bastian Eppler completed his BSc and MSc in Physics at Goethe University Frankfurt, including a year abroad at Copenhagen University. He received his PhD in Physics from Goethe University in 2022, affiliated with the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies, where he specialized in theoretical and computational neuroscience. After his doctorate, he remained in Frankfurt as a postdoctoral researcher until 2024, spending two months at the Institut de la Vision in Paris in 2023. Since 2024, he has been a postdoctoral researcher in Alex Roxin’s lab at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica (CRM).

Subscribe for more CRM News

|

|

CRM CommPau Varela

|

Trivial matemàtiques 11F-2026

Rescuing Data from the Pandemic: A Method to Correct Healthcare Shocks

When COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted healthcare in 2020, insurance companies discarded their data; claims had dropped 15%, and patterns made no sense. A new paper in Insurance: Mathematics and Economics shows how to rescue that information by...

El CRM Faculty Colloquium inaugural reuneix tres ponents de l’ICM 2026

Xavier Cabré, Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà i Xavier Tolsa, tots tres convidats a parlar al Congrés Internacional de Matemàtics del 2026, protagonitzaran la primera edició del nou col·loqui trimestral del Centre el 19 de febrer.El Centre de Recerca...

L’exposició “Figures Visibles” s’inaugura a la FME-UPC

L'exposició "Figures Visibles", produïda pel CRM, s'ha inaugurat avui al vestíbul de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística (FME) de la UPC coincidint amb el Dia Internacional de la Nena i la Dona en la Ciència. La mostra recull la trajectòria...

Xavier Tolsa rep el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona per un resultat clau en matemàtica fonamental

L’investigador Xavier Tolsa (ICREA–UAB–CRM) ha estat guardonat amb el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona 2025 en la categoria de Ciències Fonamentals i Matemàtiques, un reconeixement que atorga l’Ajuntament de Barcelona i que enguany arriba a la seva 76a edició. L’acte de...

Axel Masó Returns to CRM as a Postdoctoral Researcher

Axel Masó returns to CRM as a postdoctoral researcher after a two-year stint at the Knowledge Transfer Unit. He joins the Mathematical Biology research group and KTU to work on the Neuromunt project, an interdisciplinary initiative that studies...

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras: Open Problems, New Results, and Community

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras, held at the CRM on January 30–31, 2026, brought together experts to discuss recent advances and open problems in the field.The event strengthened the exchange of ideas within the community and reinforced the CRM’s role...

From Phase Separation to Chromosome Architecture: Ander Movilla Joins CRM as Beatriu de Pinós Fellow

Ander Movilla has joined CRM as a Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral fellow. Working with Tomás Alarcón, Movilla will develop mathematical models that capture not just the static architecture of DNA but its dynamic behaviour; how chromosome contacts shift as chemical marks...

Criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI) 2026

A continuació podeu consultar la publicació dels criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI 2026), dirigits a les universitats públiques i privades del...

Mathematics and Machine Learning: Barcelona Workshop Brings Disciplines Together

Over 100 researchers gathered at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica to explore the mathematical foundations needed to understand modern artificial intelligence. The three-day workshop brought together mathematicians working on PDEs, probability, dynamical systems, and...

Barcelona + didactics + CRM = CITAD 8

From 19 to 23 January 2026, the CRM hosted the 8th International Conference on the Anthropological Theory of the Didactic (CITAD 8), a leading international event in the field of didactics research that brought together researchers from different countries in...

Seeing Through Walls: María Ángeles García Ferrero at CRM

From October to November 2025, María Ángeles García Ferrero held the CRM Chair of Excellence, collaborating with Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà on concentration inequalities and teaching a BGSMath course on the topic. Her main research focuses on the Calderón problem,...