Excess fluoride is a global health issue. In India alone, approximately 62 million people consume water exceeding the WHO recommended limit of 1.5 mg/L. The challenge is compounded by extreme local variability: fluoride concentrations can differ drastically between wells separated by just a few hundred metres, making standardised filter design particularly difficult.

The answer wasn’t in the chemistry. It was in the mathematics.

A team spanning Barcelona and Kharagpur has published a new model in the Journal of Water Process Engineering that finally reconciles what happens in a laboratory beaker with what happens in a village filter, something previous approaches consistently failed to do. The work, led by Lucy Auton and Timothy Myers at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica, with Shanmuk Ravuru at the University of Alberta, Sirshendu De at IIT Kharagpur, and Abel Valverde at UPC, doesn’t just predict filter performance. It reveals why a century of standard models have been getting column adsorption¹ wrong.

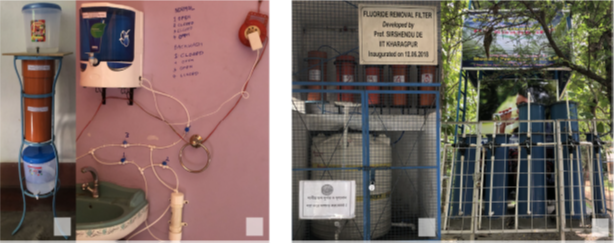

De has witnessed the scale of the problem first-hand. “Fluoride contamination in West Bengal occurs in 6 districts,” he explains. “The concentration of fluoride varies from 2.0-14 mg/L. The villagers in the affected areas have stained and deformed teeth and that was visibly pronounced.” Field samples confirm the extreme local variability the models must account for: “The concentration differs from well to well. The variation is from 2 to 6 mg/L in the same village. The concentration even gets diluted during rainy seasons.”

The Invisible Error

Myers points to a fundamental issue with how the field has approached these problems. “The problem starts with a general acceptance of old models, where researchers have forgotten the assumptions involved in their development,” he explains. “This has led to the old models being applied incorrectly or incorrectly interpreted.”

Last year, he published a critique of possibly the most widely used model for column adsorption: the Bohart-Adams model, developed in the 1920s. The mathematical derivation assumes certain terms are constant, then when fitting to data, those same “constants” are allowed to vary. “Since the derivation is in the appendix of a 1920’s paper it may not be surprising that it has been forgotten,” Myers notes. “To me the fact that ‘constants’ have to vary is a clear indication that the model assumptions are wrong. It is surprising that an obviously erroneous analysis has been applied for over 100 years.”

Fluoride-removal filters deployed across West Bengal: from early household prototypes (top left) to the commercialised version now in use (top right), and from a community-scale prototype installed in a school (bottom left) to the solar-powered community filter operating in a rural village (bottom right). Taken from [1].

For fluoride filters, this matters. The filters contain two materials: mineral-rich carbon (MRC), essentially carbonised bone meal, and chemically treated MRC (TMRC), which is coated in aluminium hydroxide. Previous models for these materials already existed, but they were fundamentally inconsistent. Researchers modelled batch experiments using one set of equations (isotherms) and column experiments using completely unrelated models (kinetics), without ensuring the two were physically coherent. Parameters that should have stayed fixed across conditions instead wandered, forcing researchers into a cycle of refitting rather than genuine prediction. This inconsistency made filter optimisation and scale-up nearly impossible.

“In fact, this is true in general of mathematical modelling, understanding the interplay between mathematics and chemistry or physics is key to producing a successful model.”

Rather than reaching for standard equations, the team began with crystal structures. MRC is mostly hydroxyapatite, the same mineral that forms teeth and bones. Its lattice contains calcium, phosphate, and crucially, hydroxide ions that fluoride can replace through ion-exchange2. TMRC adds a thin aluminium hydroxide coating that dramatically increases fluoride uptake, roughly tenfold. “There are many approximate models in the literature for contaminant capture but the process involving coated bone char didn’t quite fit with standard situations,” Myers and Valverde explain. “The data indicated the presence of multiple adsorption mechanisms rather than a single governing kinetic law. For this reason, we first examined the chemistry; by understanding the physical process we were better able to develop a suitable mathematical model.”

He adds a broader principle: “In fact this is true in general of mathematical modelling, understanding the interplay between mathematics and chemistry or physics is key to producing a successful model.” The chemistry revealed distinct reactions: TMRC undergoes ion-exchange between aluminium-bound hydroxide and fluoride; MRC does the same with its hydroxyapatite core but also physisorbs3 fluoride at vacant lattice sites. Each process operates on different timescales. Any honest model would need to capture all three.

Two Filters, One Model

Auton and the team derived separate models for MRC and TMRC from batch experiments, closed systems where adsorbent and contaminated water mix in a beaker. These batch models, grounded in chemical kinetics, established four intrinsic parameters: equilibrium constants and maximum adsorption capacities for each material.

Then came the column model, where contaminated water flows through a packed bed of the MRC-TMRC mixture. The mathematics changes. Advection⁵ and dispersion⁶ now matter, alongside the same chemical reactions.

The team developed three interconnected models, each grounded in the actual chemistry: CB-MRC for mineral-rich carbon (capturing both ion-exchange and physisorption in the hydroxyapatite structure), IE-TMRC for the chemically treated material (ion-exchange at the aluminium hydroxide coating, which provides ten times the adsorption capacity of MRC), and CB-MT for the mixed filter bed (integrating both materials with transport processes). The key insight: the four parameters from batch experiments don’t change when moving to the column model. They’re properties of the materials, not the experimental setup. Only the forward reaction rates, which depend on flow and mixing, needed refitting.

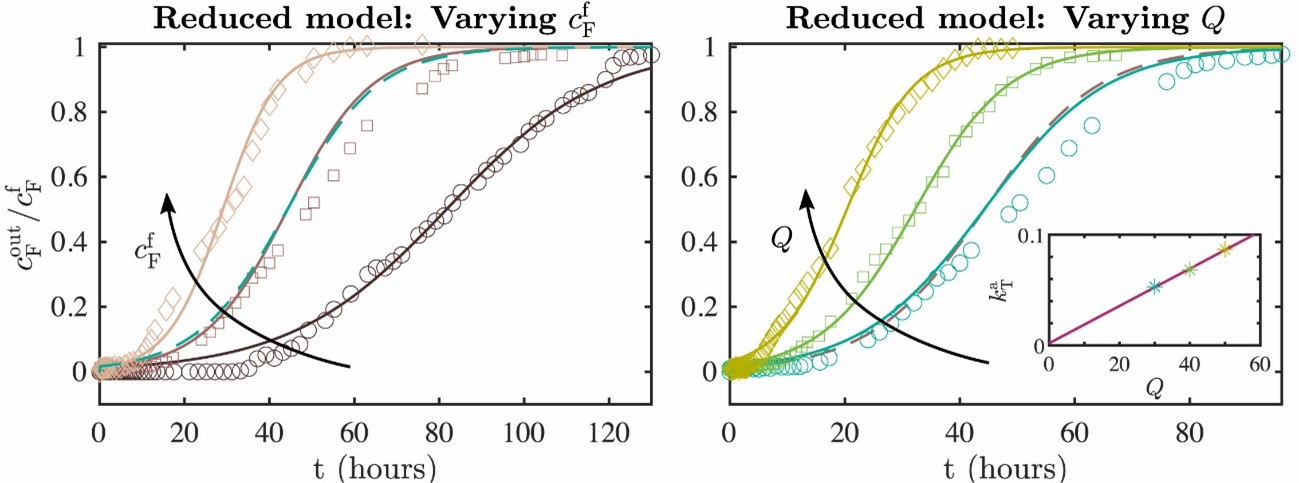

The result is a model that predicts breakthrough curves4 (the moment fluoride starts appearing in the filter outlet) across different inlet concentrations and flow rates. The coefficient of determination exceeds 0.991. The sum of squared errors stays below 6.3% of inlet concentration. When inlet concentration changes, the model predicts the new curve without refitting. The chemistry and mathematics finally align.

Breakthrough curves showing when fluoride begins appearing at the filter outlet. The reduced model (solid lines) accurately predicts experimental measurements (data points) across varying inlet fluoride concentrations (left panel) and flow rates (right panel). The model captures filter behaviour under different operating conditions using just one adjustable parameter, demonstrating its predictive power and practical utility for filter design. Taken from [1].

“In this paper we worked hard to develop a mathematical model consistent with the chemistry and experimental observations,” Myers explains. “Mathematics can help in the design of future filtration equipment but only if it is done well, is understandable to the community and is able to predict observed phenomena.”

Collaboration Across Continents

Auton visited the IIT Kharagpur laboratory, photographing prototype filters and taking detailed notes on operating conditions. Back in Barcelona, the modelling proceeded through constant exchange: questions about pH fluctuations, clarifications on grain size distributions, back-and-forth on how to interpret aluminium concentrations in the effluent.

Laboratory column filter at IIT Kharagpur used to validate the mathematical model. Contaminated water flows through the packed cylinder, with fluoride concentration measured at the outlet over time. Taken from [1].

“The first author, Lucy Auton, visited the group in India (and took the photos used in the paper),” Valverde recalls. “Subsequently we received a detailed report from the experimental team in India outlining all operational conditions and providing the complete set of experimental data. Our modelling work proceeded in close collaboration with them, and they addressed all of our questions as we developed the model and generated results.”

De describes how the partnership evolved: “Our initial collaboration was with Oxford University and one of the scientists Lucy Auton has been shifted to Barcelona and the collaboration continued there. The idea of modelling of filters was jointly proposed. It was envisaged that the experiments would be done by IIT Kharagpur and the modelling would be carried out by Lucy. The filter life can be predicted from the model for scaled up filters.”

Analysis of the full model revealed something unexpected: despite MRC outweighing TMRC forty to one, TMRC does nearly all the work. MRC contributes only at very early times and very late times, when TMRC sites saturate. This suggested a radical simplification. What if you ignored MRC entirely? The reduced model drops two of the three chemical reactions, leaving only TMRC ion-exchange. It has one fitting parameter instead of three. It still achieves R² 7 greater than 0.983. The finding aligned with De’s expectations. “It was anticipated as the treated bone char is more porous impregnated by aluminium and calcium compounds and hence has high capacity of the fluoride,” he notes. “However, since this is powdery in nature, it could choke the filter. Hence, its proportion in the mixture was identified carefully.”

“Firstly, we did not know but we suspected,” Myers says. “Experience in modelling physical problems and also techniques such as non-dimensionalisation permit us to identify dominant and negligible processes and quantify possible errors when we neglect terms. This guided us to the simplified model.” Suspicion alone isn’t sufficient. “However, whenever we present a simple model, especially to a non-mathematical community, we go to great lengths to verify it. The usual approach is to compare against a full numerical solution and also against experimental data. Only if both work well can we have confidence that the reduced model is suitable.”

The reduced model isn’t just mathematically elegant. It’s computationally cheap and straightforward to implement, exactly what’s needed for designing filters in resource-limited settings.

Where Mathematics Leads Next

The immediate applications are practical: predicting filter lifespan, optimising the MRC-TMRC ratio, designing for different flow rates and inlet concentrations. But the approach opens a broader question about systems with multiple contaminants.

“A key question we are investigating at the moment involves the simultaneous capture of multiple contaminants, this leads to a coupled system where contaminants interact and compete for adsorption sites and then some interesting new models, analysis and numerics,” Myers says. “And we don’t yet know where we are heading!”

De’s team has already begun investigating these competitive effects. “It was observed that even high concentration of calcium does not affect the adsorption capacity of TMRC and hence filter life,” he reports. “Nitrate up to 50 mg/L reduces the capacity by 5% only. Phosphate and sulphate up to 50 mg/L reduce the capacity by 10%.” However, he notes that these reductions can be compensated by packing proportionally more adsorbent in the filter columns.

Real groundwater contains arsenate, nitrate, and phosphate, all competing for the same surface sites. pH shifts as hydroxide ions are released. Temperature fluctuates. “New effects inevitably lead to more complex models,” Valverde notes. “Different contaminants, different pH will affect the adsorption and desorption processes. In addition to the higher computational cost associated with introducing new variables, mass balances, and kinetic equations, defining all relevant chemical interactions would definitely be challenging.”

The filters were already working. Now we understand why, and how to make them better.

Citation:

[1] L.C. Auton, S.S. Ravuru, S. De, T.G. Myers, A. Valverde, Development and experimental validation of a mathematical model for fluoride-removal filters comprising chemically treated mineral rich carbon, Journal of Water Process Engineering 79 (2025) 108914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2025.108914

Glossary

- Adsorption: The process by which molecules or ions from a fluid (such as fluoride in water) bind to the surface of a solid material (such as bone char). Unlike absorption, where a substance is taken into the volume of another material, adsorption occurs only at the surface.

- Ion-exchange: A chemical process in which ions of one type are replaced by ions of another type. In these filters, fluoride ions (F⁻) swap places with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) in the crystal structure of the adsorbent material.

- Physisorption: Physical adsorption where molecules attach to a surface through weak intermolecular forces (such as hydrogen bonding) rather than through chemical bonds. This type of adsorption is generally weaker and more easily reversible than chemisorption.

- Breakthrough curve: A graph showing the concentration of a contaminant at the filter outlet over time. The “breakthrough point” is when the contaminant first begins appearing in the filtered water, indicating the filter is becoming saturated and approaching the end of its useful life.

- Advection: The transport of dissolved substances by the bulk motion of flowing fluid. In a water filter, this is simply the movement of contaminated water through the filter bed.

- Dispersion: The spreading of dissolved substances in a fluid due to variations in flow velocity and molecular diffusion. This causes some mixing as water moves through the filter.

- R² (coefficient of determination): A statistical measure ranging from 0 to 1 that indicates how well a mathematical model fits experimental data. A value of 0.991 means the model explains 99.1% of the variation in the data, indicating an excellent fit.

crm researchers

Timothy G. Myers is a researcher at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica in Barcelona with over 30 years of experience developing mathematical models for complex physical processes. He serves as a Board Member of the European Consortium for Mathematics in Industry (ECMI), coordinator of European Study Groups with Industry, and is a member of the European Mathematical Society Committee for Developing Countries.

His research has advanced mathematical modelling in areas ranging from phase change and thin film flow to nanoscale optics. His current work focuses on environmental contaminants and water treatment, with particular emphasis on challenging accepted theories and developing models grounded in the underlying physics and chemistry of real-world systems.

Subscribe for more CRM News

|

|

CRM CommPau Varela

|

Trivial matemàtiques 11F-2026

Rescuing Data from the Pandemic: A Method to Correct Healthcare Shocks

When COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted healthcare in 2020, insurance companies discarded their data; claims had dropped 15%, and patterns made no sense. A new paper in Insurance: Mathematics and Economics shows how to rescue that information by...

El CRM Faculty Colloquium inaugural reuneix tres ponents de l’ICM 2026

Xavier Cabré, Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà i Xavier Tolsa, tots tres convidats a parlar al Congrés Internacional de Matemàtics del 2026, protagonitzaran la primera edició del nou col·loqui trimestral del Centre el 19 de febrer.El Centre de Recerca...

L’exposició “Figures Visibles” s’inaugura a la FME-UPC

L'exposició "Figures Visibles", produïda pel CRM, s'ha inaugurat avui al vestíbul de la Facultat de Matemàtiques i Estadística (FME) de la UPC coincidint amb el Dia Internacional de la Nena i la Dona en la Ciència. La mostra recull la trajectòria...

Xavier Tolsa rep el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona per un resultat clau en matemàtica fonamental

L’investigador Xavier Tolsa (ICREA–UAB–CRM) ha estat guardonat amb el Premi Ciutat de Barcelona 2025 en la categoria de Ciències Fonamentals i Matemàtiques, un reconeixement que atorga l’Ajuntament de Barcelona i que enguany arriba a la seva 76a edició. L’acte de...

Axel Masó Returns to CRM as a Postdoctoral Researcher

Axel Masó returns to CRM as a postdoctoral researcher after a two-year stint at the Knowledge Transfer Unit. He joins the Mathematical Biology research group and KTU to work on the Neuromunt project, an interdisciplinary initiative that studies...

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras: Open Problems, New Results, and Community

The 4th Barcelona Weekend on Operator Algebras, held at the CRM on January 30–31, 2026, brought together experts to discuss recent advances and open problems in the field.The event strengthened the exchange of ideas within the community and reinforced the CRM’s role...

From Phase Separation to Chromosome Architecture: Ander Movilla Joins CRM as Beatriu de Pinós Fellow

Ander Movilla has joined CRM as a Beatriu de Pinós postdoctoral fellow. Working with Tomás Alarcón, Movilla will develop mathematical models that capture not just the static architecture of DNA but its dynamic behaviour; how chromosome contacts shift as chemical marks...

Criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI) 2026

A continuació podeu consultar la publicació dels criteris de priorització de les sol·licituds dels ajuts Joan Oró per a la contractació de personal investigador predoctoral en formació (FI 2026), dirigits a les universitats públiques i privades del...

Mathematics and Machine Learning: Barcelona Workshop Brings Disciplines Together

Over 100 researchers gathered at the Centre de Recerca Matemàtica to explore the mathematical foundations needed to understand modern artificial intelligence. The three-day workshop brought together mathematicians working on PDEs, probability, dynamical systems, and...

Barcelona + didactics + CRM = CITAD 8

From 19 to 23 January 2026, the CRM hosted the 8th International Conference on the Anthropological Theory of the Didactic (CITAD 8), a leading international event in the field of didactics research that brought together researchers from different countries in...

Seeing Through Walls: María Ángeles García Ferrero at CRM

From October to November 2025, María Ángeles García Ferrero held the CRM Chair of Excellence, collaborating with Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà on concentration inequalities and teaching a BGSMath course on the topic. Her main research focuses on the Calderón problem,...